|

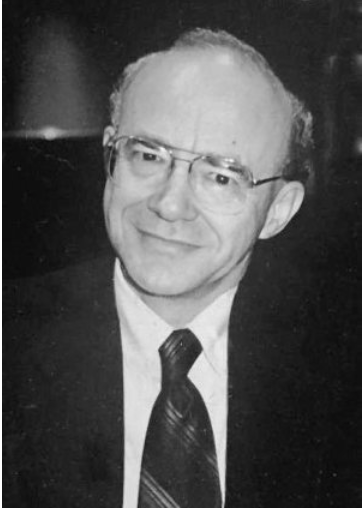

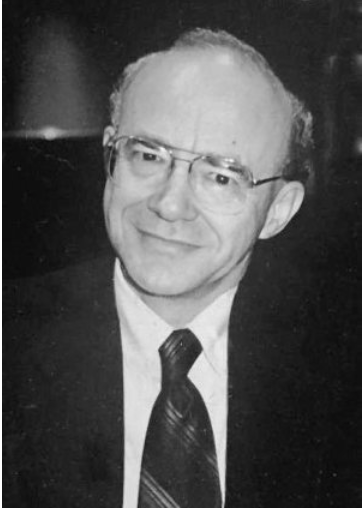

Oliver H. Woshinsky - 1939 – 2019 Oliver H. Woshinsky - 1939 – 2019

Obituary published in the Portland Press Herald, May 30, 2019

SILVER SPRING, Md.- Oliver H. Woshinsky, a revered member of the University of Southern Maine faculty for 30 years, died May 26, 2019, at 79, in his Silver Spring, Md., home, ending a valiant four and-a-half year battle with multiple myeloma. With him were the three most important people in his life: his wife, Pat, his son, David, and his daughter-in-law, Marjan.

Oliver arrived at the University of Southern Maine (then the University of Maine at Portland-Gorham) in 1971 with a Ph.D. in political science from Yale, a master’s in international relations from Columbia, and an undergraduate degree from Oberlin. He wore these impressive academic credentials lightly, once joking that he had learned as much about politics during his two years in the U.S. Army as he had in graduate school. Oliver’s scholarship was unusually wide in scope. Early in his career he studied the psychological makeup of individual politicians, devising a scheme for classifying the various “incentives” that attracted people to political life. Among those who found this work useful was his former student Kay Rand, longtime chief of staff to Maine governor and U.S. senator Angus King, who said she “always remembered his classification system for the motivations of people who serve in public office.” Later Oliver broadened his focus considerably to examine the cultural underpinnings that produce and sustain different types of governments. Whatever lens he used, Oliver’s work was always marked by deep learning, scientific rigor, and objectivity.

Despite publishing four solid books in political science, Oliver always considered himself first and foremost a teacher. The title of his 2008 book, “Explaining Politics”, perfectly summed up what he saw as his life’s mission: helping students make sense of the seemingly chaotic world of politics. Maine District Court Judge Charles Dow, who served as Oliver’s teaching assistant while in law school, described it this way: “Oliver’s work was fundamentally a quest to help people understand each other in the real world of politics.”

Coming from an impoverished background himself, and having benefited from the attention of dedicated teachers, Oliver was deeply committed to helping talented and ambitious students improve their lives. He took pride in how many of his students went on from USM to successful careers in government, law, journalism, and business, but he also cared about those who simply left his classroom as more enlightened citizens. He felt enriched by his students, and the feeling was mutual. In an article about his retirement in 2001, the Portland Press Herald reported that after Oliver’s final lecture “his students presented him with “a cake, champagne, and a standing ovation.” Earlier that day he had “kept his class of about 25 students chuckling” as he discussed “the impact - negative and positive - of the media on American society and politics.” One of those students, Kim Gruber, told the reporter, “I haven’t missed one of his classes. Every class is so informative. You can hear the wisdom in his lectures that only experience in 30 years of teaching could bring ... He’s definitely going to be missed.” A former student, Ed Lechner of South Portland, said that Oliver had “taught him and other students they could get involved in civic life,” adding, “I call my congressmen often. I drive Olympia Snowe crazy and I think it’s because of him.”

As a teacher in a state university, Oliver also considered it part of his job to share his knowledge and insights with the larger public. Reporters could always count on him for a quotable comment on current events, as scores of articles in the Press Herald archive can attest. His last op-ed piece appeared just last November. It

explained why, “in any gubernatorial election not featuring an incumbent, Maine voters will never choose the candidate of the party currently holding the governorship.”

Oliver described himself quite accurately as a “bookish, academic type,” and his quiet adult life gave no hint of its turbulent beginnings. He was born in northern China, where his father, Harry, a Jewish refugee from Soviet Ukraine, and his mother, Ada Ruth Hanson, the daughter of Methodist missionaries from Kansas, were working as journalists. In his vivid memoir, “Conflicted Legacy”, Oliver described how his parents, unsure about which rules were actually operating in war-torn China, had gone to the trouble of being married three times: once by a Soviet official, once by an American consul general, and once by Ada Ruth’s own minister father. Two weeks after Oliver’s birth, a nearby dam was blown up, either by the occupying Japanese army or by Chinese resistance forces, causing one of the worst floods in Chinese history. Later his mother wrote an article about the experience for a Minneapolis newspaper (“Marooned Mother and Baby Lived on Goat Meat, Flour.”) Oliver’s parents moved back to the United States when he was two and he spent his formative years in Vermont, including Rutland, Burlington, and Brattleboro.

As a college student, Oliver began a lifelong love affair with France, becoming fluent in its language and expert in its politics. Living in Paris in 1968 while researching and writing his doctoral dissertation, he had a close-up view of the near-revolution that toppled President Charles de Gaulle. Oliver later seized the chance to explore his Russian roots by spending a semester teaching in Archangel as part of the Portland- Archangel sister city arrangement. While there, he made contact with the children of his father’s sister, the only other member of the family who had survived the Nazi invasion of Odessa. In 2013, Oliver journeyed with some members of his extended family to Tai’an, China, to visit the site of the Christian school his grandfather had built a century before. His grandfather’s church was also still standing, and the visitors were told that it was still (or again) being used for religious services. Never content with official explanations, especially in authoritarian countries, Oliver initially was skeptical of that story. However, after doing some research he concluded that it might be true since the Chinese Communist Party “has allowed a well-supervised revival of traditional religions (and not just Christianity.)”

Oliver was a proud and loving parent to his son, David, who was born on Oliver’s 35th birthday. He and David’s mother Barbara Reisman amicably divorced after 14 years of marriage, and Oliver was fortunate a few years later to find his soulmate in Patricia Garrett, a clinical chemist who helped manage a biotech firm. During their happy 29-year marriage, Oliver and Pat cultivated and maintained countless friendships across the country and around the world. In the years of Oliver’s illness, Pat was a dedicated caretaker, proactively tracking down clinical trials in the fast-moving science of multiple myeloma. Oliver credited Pat’s scientific knowledge and advocacy skills with helping him maintain his health for as long as he did. They both also credited the strength and stamina he had developed during his 25-year jogging and exercise “career” for helping him beat back an aggressive illness for four years. He met and mentored some wonderful friends that way as well.

Son David, an architect, carried on his father’s peripatetic ways by living and working for five years in Malaysia. There he met Marjan Sedgh, a fellow architect from Iran. In 2013 David and Marjan were married in Thailand with Oliver and Pat in attendance. Despite his advancing illness, Oliver was determined to attend Marjan’s recent U.S. naturalization ceremony in New York City. Sadly, he died just a few days before it took place.

In addition to his immediate family, Oliver leaves three siblings: Margaret Grantham, Stephen Woshinsky, and Ruth Wright, and a large extended family.

A memorial service will be held in Portland on August 11th.

|