|

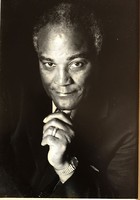

Oct. 10, 1936 – July 14, 2017

Dr. Benning was born in Omaha, Neb., the youngest of Erdie and Mary Benning’s five children. He attended Omaha North High School where he wrestled and played baseball and football before graduating in 1954.

He attended the then-Omaha University where he played football and wrestled, and upon graduation was offered a graduate fellowship in the school’s education department. He was working as director of Omaha’s Near North Side YMCA when the university in 1963 hired him as head wrestling coach — the first African-American head coach at a predominately white university in the United States. He also was the first full-time black faculty member at the school. Under his leadership, the school’s wrestling program gained national prominence and in 1970 brought the state of Nebraska its first-ever collegiate national championship. Dr. Benning was NAIA Wrestling Coach of the Year, a member of the Nebraska Scholastic Wrestling Coaches Hall of Fame and a member of the 1969 U.S. Olympic Wrestling Committee. He is a member of the Omaha University Hall of Fame and the Nebraska High School Sports Hall of Fame.

Following his coaching career, Dr. Benning went on to distinguished career in education, including nearly three decades with Omaha Public Schools. During his time as an administrator in the state’s largest school system, Dr. Benning served as an assistant principal and athletic director at Central High School, director of the Department of Human-Community Relations for OPS, and assistant superintendent. He helped lead the district’s desegregation effort and developed the nationally-recognized Adopt-a-School program. He also worked for racial equity in education including through the school district’s Minority Intern Program and Pacesetter Academy.

After leaving OPS, Dr. Benning joined the faculty at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he was the first black doctorate recipient in the university’s College of Education. At UNL, Dr. Benning was coordinator of the school’s urban education program, charged with training educators to become administrators in urban and diverse school systems. He taught at the university until his retirement in 2011.

Dr. Benning is a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps and a member of Kappa Alpha fraternity.

Donald R. Benning is survived by wife Marcidene (Dee) Benning, children Victoria L. Benning, Tracy L. Benning (Deb), Donald R. Benning Jr., Kymberly D. Benning, Damon G. Benning (Jennie), grandchildren Rayniece, Brandyn, Cameryn, Calvin, Caleb, Mya, Jordan, Micah, Breeanna, sister Phyllis Joseph, many nieces, family & friends.

Visitation Monday 9:00 AM till service time. Funeral Service Monday (7/24/17) 11:00 AM at St. John’s A.M.E. Church 2402 N. 22nd St. Private family interment. Family prefers Memorials to North Omaha Boys & Girls Club, Girls Inc., Butler Gast YMCA.

Editorial: Don Benning steered kids to brighter futures

Friends and loved ones used potent words to describe former Omaha Public Schools administrator Don Benning.

Teacher. Coach. Mentor. Father. Friend. Combined, they show the strength of a man who spent a life in service to others and who dared to go first.

Many knew Benning, who died last week, from his championship coaching of the wrestling team at Omaha University, now UNO, along with his work as an assistant football coach under Al Caniglia. He was the first African-American head coach at a predominately white university. He was also the university’s first black professor.

Benning’s strong second career as an OPS administrator also steered young people to better lives. He was assistant principal and athletic director at Omaha Central and then assistant superintendent for human and community relations.

He helped the district implement changes after a court’s desegregation order. He helped recruit teachers of color. He mentored at-risk kids. “He was very concerned that all students were treated fairly and receiving the kind of opportunity the district should offer them,” former OPS Superintendent Norbert Schuerman said.

To people like Curlee Alexander, retired Omaha North wrestling coach, Don Benning was more. Alexander was one of many who credited Benning with helping him graduate from college.

Those who coached with Benning and those who played and learned under him remember an intense man with the ability to see people’s strengths.

He was a forceful advocate for the young whose legacy lit the way for kids to brighter futures. Omaha was lucky to have him.

Don Benning remembered as first full-time black faculty member, wrestling coach at Omaha University

By Stu Pospisil and Erin Duffy / World-Herald staff writers

Don Benning was a groundbreaker in academics and athletics.

First black faculty member at the University of Omaha, now UNO.

First black head coach at a predominantly white university in the United States and the first to lead a team to a national championship. UNO’s 1970 NAIA wrestling team won the state’s first national title in a college sport.

First black doctorate recipient in the NU College of Education.

First black athletic director at an Omaha Public Schools high school, Central, and the first recipient of the state Athletic Director of the Year Award.

First black U.S. Olympic wrestling committee member.

Benning, 81, died Friday of multiple health issues stemming from kidney failure. Services were being planned.

“He was fearless,’’ son Damon Benning said. “He had laser-sharp focus. The worse the conditions, the better he was.

“He was so others-centered. So unselfish and would do anything anybody asked of him. It was so strange because he was such a man of principle. He had this way of having conviction but being so unselfish. That’s a rare combination. Usually one is at the expense of the other.”

His father’s career touched many.

“He made my life,’’ said Curlee Alexander, retired Omaha North wrestling coach. “If it hadn’t been for him, I wouldn’t have graduated from college.”

The youngest of Mary and Erdie Benning’s five children, Don Benning grew up in the Sherman Elementary neighborhood near 16th and Fort Streets. At Omaha North High he wrestled and played baseball and football before graduating in 1954.

In a collection of autobiographical essays, “Better Than the Best: Black Athletes Speak, 1920-2007,” Benning said he considered baseball his best sport and played on the Woodbine (Iowa) Whiz Kids semipro team with future Hall of Famer Bob Gibson.

Iowa State University wanted him to walk on for wrestling, but the family couldn’t afford it so he enrolled at Dana College in Blair, Nebraska, for one semester before transferring to Omaha U. The fullback had an injury-plagued football career with two knee injuries, the latter in the first game of his senior season as a co-captain, and a broken wrist.

Benning had only one wrestling season, when Omaha U. reinstituted the sport in his senior year. He was undefeated, but the Indians bypassed the 1958 NAIA nationals.

He was going to teach in the Chicago Public Schools before Omaha U.’s president, Milo Bail, offered him a graduate fellowship in the education department for two years.

Benning was acting director of the Near North Side YMCA when Omaha U. hired him in 1963 to be wrestling coach and an assistant in football to head coach Al Caniglia, who also had been the wrestling coach.

“I took over the reins ... knowing full well I would be closely watched,’’ Benning said in his autobiography.

His teams at Omaha U. and UNO had an 87-24-4 mark, including 55-3-2 during his final four seasons. After finishing as runner-up in the NAIA nationals in 1968 and 1969, the Indians won the title in 1970 at Superior, Wisconsin.

“When I took the job I wanted to keep the program at the level he had built it up to,’’ said former UNO coach Mike Denney, who followed Benning’s successor, Mike Palmisano.

“I wanted him and his guys to feel like they were part of what we were trying to do.”

Alexander, a year removed from an individual NAIA title, was a graduate assistant under Benning in 1970.

“He gave me all the opportunity and guidance to be a success,’’ Alexander said. “A lot of what he taught me I continued those things through my career. He taught me how to be a teacher, how to be a man.”

Benning left coaching and UNO after a third-place finish at nationals in 1971 — saying later that he wanted to spend more time as a parent — to be assistant principal and athletic director at Omaha Central.

Thus began the second act of Benning’s career. He spent 26 years in OPS, retiring in 1997 after 18 years as an assistant superintendent for human and community relations.

When he retired — a decision made in part because he felt he was passed over for the superintendent job that ultimately went to John Mackiel — he was OPS’s highest-ranking black administrator.

“He was a beacon of light for the Omaha Public Schools and the Omaha community,” North Principal Gene Haynes said.

Benning worked on several high-profile initiatives, including the district’s court-ordered desegregation plan, an Adopt-A-School program that connected businesses and schools and a minority teacher recruitment effort.

Colleagues say he had a strong moral code and sense of justice.

“He was very active in the desegregation program, he was very concerned that all students were treated fairly and receiving the kind of opportunity the district should offer them,” former OPS Superintendent Norbert Schuerman said.

Schuerman, who led OPS for 13 years, said Benning had an opinionated and forceful personality that made him a strong advocate for kids and ensuring equity across schools.

“He was strongly committed to doing what was right for the young,” he said.

Ken Butts worked as an OPS projects coordinator for roughly 20 years under Benning.

Butts said Benning was often at the forefront of fielding parent questions and concerns about the desegregation plan. He held high expectations for the employees who reported to him, but balanced that with warmth and a sense of humor.

“He really cared about the students, about the families, about the community,” Butts said. “He wanted to make sure that the school district did everything within his power to meet the needs of our diverse student body, especially our students who were marginalized.”

Benning went on to teach the next generation of educators at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He worked in its educational administration department from 1997 to 2011.

Brent Cejda, a professor and department chair, said Benning was “the most respected man I’ve ever met in my life.”

Benning was an instructor when Mike Lucas, the superintendent of York Public Schools, was working on his doctorate. Benning’s influence rippled out far beyond Omaha, he said.

Benning oozed pride for OPS and was constantly being stopped in the street or greeted by someone he knew, Lucas said.

“It was like walking around with one of the Beatles or a movie star,” he said.

Benning’s love of football ran deep, and Lucas would often see him skipping lunch to watch “whatever cruddy game was on ESPN2” in the Nebraska Union.

“There were probably 18 of us in the class and we stayed together for three years, and he just made each one of us feel like we were the most important person in the class,” Lucas said.

At a dinner three summers ago, Benning gathered with his 1970 UNO wrestling team for one of the last times. The Indians’ white 167-pounder, Rich Emsick, got up to sing “The Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me” to Benning.

Emsick, who died in 2015, told The World-Herald that night: “I am marveled, or just amazed, when I hear the history of the ’60s and what some of the black people went through at that time. We had none of that. None of that was in my family, and none of it was in the room. ... Everybody was so together, just like we are now. The family.

“That man did it. He took you under his arms and wanted you to be the best you could possibly be.”

Besides his son, a former NU football player who is an Omaha sportscaster and talk-show host, survivors include his wife, Dee; daughters Vicki, Tracy and Kim; and son Don Jr.

|