Recap of the 50th

This is a page that has information from our 50th Reunion. The information below on this page is:

Ordering information of the Video of this Reunion, Download Link for photos of this reunion, Ordering information of the 1994 Reunion Video, Don Anderson's Speech, Names of those that attended this reunion.

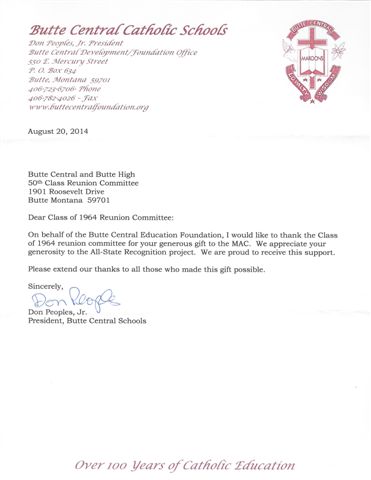

1. Thank you letter

2. Ordering the Video of this reunion.

Contact Raines Video Production directly and purchase it from them. Price shoud be about $29.95. Contact information is Raines Video Production 818 SW 3rd Ave #258, Portland, OR 97204, Ph: 1-800-654-8277, or www.rainesvideo.com

3. Downloading photos link or Purchase a Printed Photo

You can send us photos to share at butteclass1964@gmail.com

and we will save them on the link below to share.

You can download photos

from the following link and take them to your favorite place to print your own copy.

https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B1eSVJyhvwwLN1E4LWhVTE8wVVU&usp=sharing

The combined class pictures need to be printed as a 8x12 so no one is cropped out

If you wish you can print them larger than 8 x 12

or

e-mail scpaffer@charter.net

phone number - 406-782-0226

4. Ordering information of the 1994 Reunion Video

We have the 1994 Reunion Video transferred to 2 DVD's. The first one has scenes around Butte that have been gone for a long time. The second one is the McQueen Club and Peterson's Ranch. The price of the 2 DVD's is $5.00 plus shipping. Contact Butte Stuff at 1-406-490-3681 or email Cheryl Acherman at buttestuff.com

5. Don Anderson's Speech

We all had a wonderful time. This is the speech that Don Anderson gave to us on Saturday. It was a wonderful talk and we thought we would share with you his words.

Donald Anderson

Pentimento

Pentimento is an Italian term that can refer to painting. It is the underdrawing, the original layer of paint upon which other layers are added, often at later dates. The pentimento of the painting of our lives is our birthplace. There is no avoiding your birthplace. It is where your memories begin. For us that zip code is 59701. Butte, of the Montana sort. I left Butte in 1965, one year after leaving Butte High. Since, I have seldom visited: a funeral, two high school reunions, a couple of summer drives. Three-fourths of my life has been lived elsewhere. Yet, when I sat down to start my last book, I kept returning and referring to my pentimento, my Butte. We cannot, any of us, escape our founding inner landscapes. They inform our personalities, our values and desires, our fantasies and needs—it’s where and how we started. It is a fact that amnesia is cruel deception, for to not know who we were is to not know who to be. It’s true of cities too. . .

As many of you know, Butte was once the largest city between St Louis and Seattle. In 1867, the peak of the placer boom had the city’s population at 500. It halved over the next two years. Then, quartz deposits were discovered. Based first on silver, then copper, mining barons became Montana’s first millionaires. In 1884, there were 300 operating mines, 4,000 posted mining claims, 9 quartz mills, and 4 smelters, all operating 24/7, making Butte the planet’s largest producer of copper. In 1899, Marcus Daly merged with Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company to create the Amalgamated Copper Mining Company. 1901: The Montana Legislative Assembly passes the Eight-Hour-Day. Within three years, Butte claims the largest payroll in the world—12,000 men in the mines and mills with a payroll of $1,500,000 a month. By 1910, having bought up the smaller mining companies, Amalgamated changed its name to, as you know, the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, the largest corporate power in Montana. Through the 1950s, the Company owned every newspaper published in the state.

Three Heavyweight Boxing Champions: John L. Sullivan, himself, as well as Jim Jeffries and Bob Fitzsimmons all fought bouts in Butte. Holding the record for the lowest winter temperature (-61° F) in the contiguous United States, Butte is where J. Edgar Hoover assigned FBI agents who nettled him.

Harry “Swede” Dahlberg was our high school gym teacher. Coaching four sports (for more than 40 years) his teams won 26 state championships. In the 1960s, he coached track and taught gym. A child of the 19th century, he served in the Navy in The Great War and was an Army PE instructor during World War II. Heading toward 70, Coach Dahlberg performed 50 perfect pushups at the beginning of each gym class, and would converse while he did his pull-ups. “Dry your face before your ass,” he advised.

I didn’t miss Butte when I lived in France, right after high school. There were too many distractions, not the least of which was the French language itself that rushed at my ears like static. It was in France, though, where at 19, I met who seemed to me the most sophisticated woman I’d ever encounter. How sophisticated for the lad from Butte? Well, she spoke French and smoked cigarettes. She was 17.

My first Air Force assignment was in Biloxi, Mississippi. I reported in the summer of 1971, the same year Coach Dahlberg died. Having spent the bulk of my life in the Rocky Mountains I was unprepared for a humidity that proved physical, an objection impossible to refute. In Butte, no one had air conditioners in their houses or cars. I couldn’t understand Mississippi. Why had we fought for the South. What could that have been about? In Biloxi, when the sun went down, it got hotter.

I missed Butte too when the Air Force assigned me to Strategic Air Command Headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska. I’d lived most of my life at the base of the Continental Divide in Montana, where the sun rose from behind and set upon peaks. In Nebraska, the sun didn’t know where to be.

My father’s father, James Arthur Anderson, owned family land near Moab that he lost in a poker game to a Utah judge. To remedy this loss, he made and sold Prohibition hooch to Jack Mormons. In time, his selling to Utes on the reservation set the Feds on his trail. Loading up Grandmother LeVone, my father and his sister, Ramona, he headed north. When they ran out of gas in Montana, they parked, which is why I’m from Butte. A Mormon bishop had warned my grandfather about the Feds.

My grandfather claimed Jack Dempsey fought Jess Willard in 1919 for the Heavyweight crown with cracked ribs, and that he, my grandfather as a sparring partner, had cracked them. He also claimed to have witnessed Jack Dempsey bend a horseshoe flat with his hands. And he told me stories of his days in the Yukon when he was just a few years older than I when I was listening. As I heard it from him, my grandfather pretty much walked to and from Alaska.

As an adult, I did and didn’t want to confirm my grandfather’s story about his sparring with Jack Dempsey. As it turns out, my grandfather was the right age to do it and was then living in Colorado, a train ride to Manassa, from where Dempsey hailed.

When my father was a kid, he watched his father defeat a local tough. In a ring in the Butte Civic Center, my grandfather stepped through the ropes in his work shoes and stripped off his shirt. He wore long pants and a belt. Gloved-up, he took more than he gave, then one-eyed—one eye punched shut—jockeyed a right that knocked a fighter called Dixie LaHood senseless. In the center of the Depression, my grandfather stepped out of the ring, bare-chested, took his shirt and earnings, then walked home with my father, his son. How many chances like that does a father have?

Instead of working in the mines in Butte, my grandfather would don boxing gloves and battle. Paydays, he would show at a mine at the shift change to challenge all-comers. Someone would pass a hat and the winner would walk with the cash. My grandfather made a living this way, or at least what he needed to fuel the cards and the booze.

“Kill the body, the head dies,” my grandfather informed me on the day he left our house for the County Home. Quoting Joe Louis, he had handed me his boxing gloves. They weren’t pillow gloves; they were thin as winter mittens. Mitts on, I felt dangerous. Along the cracks in the gloves ran slivers of a color like rust, as if it were blood and not time that had broken the leather. My grandfather kept his boxing gloves on a hook near his bed, as if ready for business.

These are the kind of stories that Butte is built on, aren’t they? A different breed of people here. Stronger folk. Resilient. Larger than life.

Butte’s Miners’ Union formed in 1878, sending the largest delegation to the International Workers of the World’s founding convention in Chicago in 1906. Butte became known as the “Gibraltar of Unionism,” but worker frustration at the Company’s deaf ear to demands led to violence in 1914 and 1917, violence involving guns, dynamite, Federal troops, and murder. In a singular case Butte’s mayor shot and killed Erick Lantilla, a Finnish miner, after the disgruntled Finn had stabbed the mayor.

In 1917—the city’s population at a peak of 100,000—168 men were killed in a mine fire: a fire that remains the worst disaster in U.S. mining annals. A frayed electrical cable being lowered down the main shaft sparked the dry timber lining. With the Great War clamoring for copper, all of Butte’s mines were working at capacity, and the Speculator mine had nearly half its 2,000 miners below ground when the fire struck, scattering flames down the shaft and into the drifts and crosscuts.

Two years before the Speculator calamity, 16 shift bosses and assistant foremen who had surfaced for their lunch stood around the main shaft of the Granite Mountain mine awaiting the 12:30 whistle as the signal to return underground. Also awaiting descent were twelve cases of dynamite. Just as the whistle blew, so did the powder. Fingers, identified by rings, were found a mile distant.

1964: I graduated Butte High and my father, as he’d promised, got me on at the Mountain Con, the mine where he was employed as safety engineer. My first job was assisting a contract miner whose regular partner hadn’t shown for work the day after payday. I’d stood that day in the rustling line and was hired for a pre-determined day’s pay of 21 dollars. I went to work with the miner, mucking out a stope that had been drilled and blasted the shift before.

Our mucking machine, like everyone’s, powered by hydraulics, was a scoop—a steel bucket on cables and pulleys rock-bolted into the face of the stope. When the cable snapped, my partner and I dragged it, like road kill, to the tracks where we laid it on one of the ore car steel rails. Here, he meant to trim the frayed ends in order to re-splice them. My partner knelt by the rail and arranged the heavy snake. I handed him the axe.

I was asking questions and, in the process of answering me and trimming the cable, the man lopped off his left index finger. It was a powerful swing and a clean cut, just shy of the knuckle, toward the wrist. The man removed his glove to stanch the bloody pump. He didn’t shriek when the axe fell or when he observed the result. He wrapped the wound with shirt cloth he’d torn away with one swift move with his good right hand. Shit, he murmured, then rose to stand in his half shirt. He could have been a statue, a bronze man in a helmet, a hero, an actor in a movie starring Victor Mature. The miner’s reaction made me think of Ulysses or Samson.

I stooped to retrieve the digit. It was still in its little glove case, like a gift jackknife. We headed for the station, where a massive box constructed of lagging housed coils of pipe through which water flowed for drinking, for drilling, and for quelling dust. Each morning, on each level of the mine (we were on the 5200 level, a mile deep) block ice was shipped down and dumped into these boxes to chill the water.

I had carried the axe, and chopped on a block for ice to fill my hardhat. I dumped the finger from the glove, then covered it with ice.

At the lighted station, we rang for the cage. My father, in his role as safety engineer, arrived with the shift boss. He transferred the finger and ice to his hat. My partner, my father, the shift boss, and the iced bone and flesh were hoisted up. My father congratulated me for thinking of ice. He called me Donnie in front of the men.

I reattached the lamp to my hardhat and hoofed it back to the stope and the cable. There were ice chunks caught in the hardhat webbing. I stuck two pieces in my mouth. I ate lunch, then looked at my watch and waited. Temperatures at 5200 feet were generally in the 90s. I was sweating when I saw light approaching. I guessed it was my father coming to check on me, but it was my partner. He had been to St. James Hospital where his finger had been reattached.

My partner walked me through resplicing the snapped cable, and we went back to work with me operating the mucking machine. In the middle of it all, I shot my partner a look. Didn’t want to miss the shift, he said. He held the ungloved hand in front, as if to know where it was. Its wrapping shone white in our lamplight.

On some level, I suppose, I knew then that I wasn’t tough enough for Butte. I remember that consideration. I remember, too, that families had charge accounts at grocery stores to be paid on paydays, and that doctors would visit houses. I remember my mother bathing me in the tub before delivering me to St. James where a Swiss doctor lanced my eardrum. Yellow pus sprang into the air, coating the doctor’s sleeves. I experienced immediate relief. I may have been 11. My overnight roommate was a 17-year old who was to die from kidney failure. He was kind to me, like an older brother concerned for my health. I read in the newspaper that he’d been a pole-vaulting champion at Butte’s Catholic High School, Butte Central. His hair was short, a brush cut.

A few years after, Eddie Turner, Jackie Baker, and I lobbed dirt clods at Mrs. Lorango’s wet sheets every wash day until we got caught. We were surprised that Mrs. Lorango knew we were the throwers and that our parents, without checking with us, believed her. We’d hid behind a berm in the cow pasture where we pretended we were pulling grenade pins with our teeth. Who was I, if not Vic Morrow, starring in COMBAT!?

Remember the winters? Anyone who does not believe that the Earth is warming didn’t live in Butte fifty years ago. Or sixty, or a hundred. In 1938, a spring snowstorm paralyzed Butte. Snow fell for 80 hours. A year earlier, one day in January it was 40 degrees Fahrenheit. The next day it was 40 below.

A year or two back in Colorado (where we have lived for 25 years), I tore off my side-view mirror on a concrete pillar in the underground garage where I work. On a blizzard day—18 inches of snow and high winds—schools and government offices had closed, and I was home from work. I called WRECKMASTERS: Wreckmasters—Jimbo here. “So you’re there,” I said. “I wondered.” Our kind of weather, Jimbo said. I felt back in Butte.

Though we lived within Butte city limits, we owned a cow, an old Guernsey we kept in a bathroom-sized pen with a bathroom-sized shed in the backyard. The cow’s name was Pet. When I milked Pet, she’d swing her shit-grimed tail. Pet’s tail was a redhead’s dirtied tresses encircling my neck and face, my ears and mouth. It was best to keep your trap shut. The idea I had was to shave the tail. Problem solved, I sat to milk. When Pet swung her tail, the rope of it nearly knocked me deaf. For a while, I wore earmuffs and goggles.

In the barn, where we milked the cow, I sequestered Police Gazettes and the lingerie pages from the Sears catalog. The Police Gazette contained blurred photos of strippers and whores and lurid stories about murder and sex. Whence the Gazettes? Were they my father’s? The pages from Sears, I tore out myself.

There was a mining engineer who would stomp through my father’s mining office with his night crew. This engineer had taken to sitting in my father’s chair and propping his cruddy boots on the desk. My father told him if he did this again he was going to knock him to the floor. I’d heard my father set forth the situation to my mother. My father worked Saturdays at the mine, above ground, for half days, and I often tagged along. In my father’s office, I’d fiddle with ore samples (I’d assembled a labeled collection—pink manganese, cobalt, iron pyrite, quartz, zinc—in an egg carton for a Cub Scout badge), and sharpen pencils. Sometimes, my father would let me wash up his respirators in a big sink and install clean filters. I’d draw with my father’s drafting tools.

The Saturday I’m writing about, we entered the office to see the engineer in my father’s chair with his feet on the desk. When my father kicked the castored chair, the engineer and his elevated feet crashed to the floor. My father jutted his chin toward the slime on his desk, then handed the man a pair of red boxing gloves. He had removed two pair from his desk’s bottom drawer. Where had those come from? I had not known that my father worked in a place where boxing gear was essential. Whatever the case, he educated the engineer that Saturday, conducting a clinic in fisticuffs. Right away he landed one on the nose—a quick flick with his shoulder behind it. And if the snapped nose hadn’t diluted the big man’s starch, what my father next did to his ribs did. The clinic was almost over before it started. Everything my sweet-tempered father did was exact and quick and vicious.

There were no policies against livestock in Butte. Because I so hated milking, I dreamed of the sheriff coming to our house to tell my father it was illegal to keep cows. I didn’t hold out much hope because at school we studied Montana history and I knew there were more cows in my state than people, and my teacher had said that Montana statutes dictated death by hanging for cattle rustling, but not for human murder.

Miss Stephanie, my fifth-grade teacher was from California. She said San Francisco housed more people than our whole huge state, but then admitted that San Francisco couldn’t have penned all the cows. Your cows was the way she put it.

If it was my sisters who named our old Guernsey Pet, it was my father who named our new cow: Marilyn. He kept a pin-up calendar in his bureau’s top drawer. The twelve months of Miss Monroe confirmed a penchant for chests and black-mesh nylons. Old Pet had been put down and my father bought a two-acre field across from our house. The Silver Bow creek ran through the field. Encircled by barbed wire, the two acres featured a tin-sided shed, a manger, and the berm from behind which we lobbed our dirt clods at the wet sheets.

It was my job to shepherd Marilyn to the stockyards—a one-man, single-cow cattle drive. You want your friends to see you walking a cow to the stockyards to be bred? You’re 16 years old. You live inside the city limits. In a fenced field across the street from your house is a cow your father wants humped. You’re driving a cow with a stick in your hand. You’re herding a cow with a stick to the stockyards.

The bull is let in. Cowboys materialize and arrange themselves all along and on the corral’s top rails. The bull, short-legged, has a hard time reaching. There are jokes. When the bull connects, everyone cheers, so you nod your head, squint. Your father pays someone. You find your stick and start the cow for home. The old girl seems bedazed and druggy.

I am, as many of you, a boomer of the 1946 sort, all consequences of Armistice. And, as of 2009, with my mother’s death, I am officially a boomer orphan, which also makes me, like Dahlberg approaching 70, now old enough to dispense advice. So I’d like to conclude tonight, with a little piece I published a few years back. I’d entitled the piece “Advice,” which the Canadian publisher deemed cliché-ish, lame, boring. . . The piece was retitled from “Advice” to “Should You Experience an Erection Lasting More Than Four Hours . . . and Further Guidance.” What follows is most of what I’ve learned since high school:

Don’t eat at a place called “Mom’s,” don’t play cards with a man named “Slim,” and don’t go to bed with a person who has more problems than you do. Don’t stick your fork into a toaster. Warned not to attach my tongue to metal in Montana during winter, I began eyeing the galvanized posts on the grounds of a house I passed on my way to Emerson Elementary. The mercury registered 30 below when I chaperoned my experiment. Then this: I did not stick a fork into a toaster; I stuck it into an outlet (lacking forks, a magnet will do!). Why saddle your kids with names like “Apple” or “Willow”—“Harley,” “Hubcap,” “Lug-nut,” “China,” “Bubbles”? Give attention to warnings: You could lose an eye. If I have to stop this car. Fragile. Give attention to what you read. Graham Greene: Innocence is like a dumb leper who has lost his bell, wandering the world, meaning no harm. Russell Banks: Fear of losing a woman and loving her are not the same thing. Albert Camus: It is all practice: when we emerge from experience, we are not wise but skillful. But at what? Frederick the Great: Artillery lends dignity to what might otherwise be a vulgar brawl. A professor friend may be plagiarizing when he says academics have more fears than medieval peasants, but the line sounds trusty enough to steal. William Burroughs was for thieving and against paraphrasing altogether. Trust haiku. A good chili requires cumin (or Italian sausage containing cumin). What the FBI said: Serial killers target Rest Stops. Hydraulic mining pollutes watersheds, kills fish. Lewis Grizzard: Instead of getting married again, I’m going to find a woman I don’t like and give her a house. Use Less Stuff. For a meal of SHEEP’S HEAD: Split head and remove eyes. Remove brain and soak in vinegar and water. Soak washed head in salted water. Blanch head. Boil (gently) brains. Scrape meat from head. Skin tongue and cut in slices. Add meat, tongue, and brains to white sauce. Reheat and serve with toast points and minced parsley. Walk with scissors. Remember the Alamo. Remember Oppenheimer. A woman without a man is like a fish without a bicycle. Remember Steinem. A’s hire A’s; B’s hire C’s. Humility is no substitute for a good personality. DON’T argue with Fran Lebowitz. Consider this distillation:

WHAT PEOPLE SAY

Below you will find the complete and unabridged record of the general conversation of the general public since time immemorial:

a. Hi, how are you?

b. I did not.

c. Good. Now you know how I felt.

d. Do you mind if I go ahead of you? I have only this one thing.

What to engrave on your tomb: I told you I was sick. Shun platitude. William Stafford: Some haystacks don’t even have any needles. Admire Oscar Levant as he condenses Doris Day: I knew her before she was a virgin. A favorite teacher, poet Edward Lueders observed: What antique superstition stands behind the notion that damn and hell are bad words and that kill and murder are not? Certainly rape is a more obscene concept than fuck. Why then do we not consider it a more obscene word? What I learned in the military: Nothing is impossible to people who don’t have to make it come true. And Anatole France: To die for an idea is to set a rather high price on conjecture. On his other hand: There is a certain impertinence in allowing oneself to be burned for an opinion. Nietzsche understood that the trouble with war is that it induces stupidity in the victor and vengeance in the vanquished. Before we made fire, before we made tools, before we made weapons, we made images. Art, at its deepest level, is about preserving the world. John Cheever: Avoid kneeling in unheated stone churches. Ecclesiastical dampness causes prematurely gray hair. Milan Kundera: Nothing beats an argument from personal experience. Pack Tabasco for long trips to remote locations. If you were blind, would you be in love with a different person? Approaches: Don’t talk to pit bull owners about pit bulls—they don't know what you're talking about. Always bet on black. Let your children paint their bedrooms. Edward Lueders: Character is determined by what one respects; the rest is a personality or style. Style is a matter of how you handle things. It is movement, touch, arrangement, speed, care, and carelessness, not just how you handle words, but how you pick up a child, pet a dog, or make and throw a snowball. My wife’s step-great aunt died in a nursing home where she had lived in her own apartment. While settling her affairs, we lived in that apartment as the rent had been paid through the month and was not refundable. What will not occur in a nursing home shower: (1) You won’t be scalded; (2) You won’t drown. Esteem agreeable bumpers: JESUS Loves You. Every One Else Thinks You’re An Asshole. Don’t eat yellow snow. Had my first wife asked once more: Is that a joke?—I would’ve had to have had her killed. ARGUMENT: Marry someone who thinks you’re hilarious. Which counters my father’s advice about broads: Eat crow. An apple a day. Don’t buy surplus ammo from India. If nine Russians tell you you’re drunk—lie down. What to do: Give your love a cherry that has no stone. The power of the atomic bomb comes from the forces holding each atom of substance together. What the doctor said: If you experience sudden loss of vision, stop using Cialis. Keep in mind that the nearest exit may be behind you. Don’t immerse in water. Stand up straight. Floss.

Please visit Donald’s website at Amazon http://www.amazon.com/Donald-Anderson/e/B00CPWGZVE

6. People that Attended our reunion

We will be listing below the people that attended. This is the old list that we need to double check.

BUTTE HIGH & BUTTE CENTRAL 50TH REUNION ATTENDEES AS OF 6/14/2014

ANDERSON DONALD - BH

BAJOVICH NANCY GRIGSBY - BH

BARNICOAT CAROL BLEWETT - BH

BARGER CAROL HOLLAND -BH

BAY LEAH ZOLYNSKI - BH

BELANGER RUSS - BC

BENDER RON - BC

BENNETT LINDA - BH

BERRYMAN MARGARETTE DAHL - BH

BERRY JIM - BC

BLANKMEYER JON - BH

BONTEMPO MARGIE SCHENK - BH

BOUNDY JUDY RICHARDSON - BH

BRANCAMP BILL - BC

BRINEY JIM - BC

BRUNNEL MARY RUTH BERRY - BH

BUTALA LOU ANN ELIASON - BH

CADDY SUSAN O'BRIEN - BH

CANALIA GERRI ERSKINE - BH

CARVETH JACK- BH

CAVANAUGH JOHN - BC

COHEN DAVID - BC

CONWAY PEGGY RIPKO - BC

CRADDOCK JUDY ARCHER - BH

CRAIN KAREN WALSH BC

CRAWFORD JERRY - BH

D’ARCY JERRY - BH

DE GEORGE CAROL STERLING - BC

DI FRONZO MICK - BC

DOUGHERTY STEVE - BH

EVANS GARY - BH

FANNING CAROLE - BH

FANNING MARGIE WELTER - BH

FARREN BOB - BC

FITZPATRICK KATHERINE (KATIE) JAMES - BC

FRASER BILL - BH

GALLAGHER BILLIE SHOVLIN - BC

GILMORE KATHY OING - BH

GLENNON KAREN - BH

GOODMAN BILL - BH

GORDON MICK - BH

GRANGER BEV YORK - BH

GRANT BILL - BH

HALE JIM - BH

HANPA NORMAN A - BH

HARRY KAROLEE QUILICI - BH

HARVEY JOHN - BH

HASER CHERI SMETANA - BH

HASKINS ED - Unable to Attend - BH

HINCH LYNN - BC

HOLLAHAN LORETTA MALONEY - BH

HOOPES CLIFF - BH

HOUTS CHERYL SCHWARTZMILLER - BH

HUNGERFORD ANDREA MEAD - BH

IHNOT PATRICIA - Unable to Attend - BC

JACKSON SUE GERRY - BH

JOHNSON GLENN - BH

JONES PATSY KURILICH - BH

JONES RICH - BC

KELLY JOHN - BC

KLABOE JUDY RUSSELL - BC

KNEEBONE DENISE PEDERSEN - BH

KRAUSE SUZE - BC

KRUZICH TONY - BH

LAITY TOM - BH

LAWRENCE TOM - BH

LEIPHEIMER BOB - BH

LEMELIN CHERYL GRANT - BH

LEPROWSE DIANE CHIAMULERA - BH

LEPROWSE JIM - BH

LEPROWSE WALT - BH

LILLEY NORMAN - BH

LOCKMER ANN MARIE CARTER - BH

LOMBARDI LINDA FACINCANI - BC

LOUGHRAN DIANE JONES - BH

LOWNEY RON - BH

LYNCH EILEEN ROSS - BC

MACK MICHELLE SWANSON - BC

MACKEY DARRYL - BH

MALKOVICH DAN - BH

MILASEVICH JO ANN ROLLES - BH

MC GRATH MARY - BH

MC CARTHY TIM - BC

MC COY DANANE PIERRE - BH

MC GARRY MARJORIE APPELMAN - BC

MC GLOIN TOM - BC

MC GONIGLE MICHAEL - BC

MC GUINNESS PAT GIBSON - BH

MC LEOD KEN - BH

MC KIERNAN DAVE - BC

MELLOW RENEE BUCKLEY - BC

MERRETT CAROL GILBERT - BH

MICHAUD CAROL GRINER - BC

MIHELICH SANDI JAKSHA - BC

MILES JILL MILES-DAVIS - BH

MILLER CAROL WALINGSHAW - BH

MISCHKOT JIM - BH

MOULDER ELLEN HANPA - BH

MULCAHY PAT - BC

MURPHY JOHN EMMETT - BC

NELSON BOB - BH

NICHOLLS PHILP - BH

NIELSON RON - BH

NORINE ROBERT - BH

O'CONNELL DOUG - BC

O’CONNELL WALLY - BH

O'CONNOR SHARON MALKOVICH - BC

O'MARA CAROLYN - BC

OSSELLO JACK - BC

PARKER KIELY - BC

PATRICK JUNE LINDQUIST - BH

PENETCOST MARY LARSEN - BC

PETERS SHARON JOHNSON - BH

PHIPPEN TERI LEPROWSE - BH

PLATE BONNIE LUNDBURG - BH

PLESSAS DON - BH

PLUTE DON - BC

POTTER JACK - BH

RAFFATH DAVE - BH

REAUSAW SALLY PERINO - BH

RICHARDS RENA BUCHER - BH

RICHARDS SHIRLEY LANDON - BH

RICHARDSON PAT - BH

RICHTER BEVERLY LEAN - BH

RITCHIE LORI HOWARD - BH

ROBERTS MARY ANN KERNS - BC

ROLANDO JIM - BH

RONNING KEN - BH

ROSS PHILLIP JACK - BH

ROWE CAROL SHEA - BH

ROWE LLOYD - BH

RULE MARY LOU FARREN - BC

SALLEE NANCY - BH

SALUSSO MARTIN - BH

SCHMITT GLENDA LAMMI - BH

SEBENA DAN - BH

SHEA JUDY SCHWANKE - BC

SHISKER JOANN SHAW - BH

SHOVLIN ANN MARIE FIELDS - BC

SHOVLIN MARJORIE MC GINLEY - BC

SHURTLIFF LINDA KEHOE - BH

SMITH DENNIS - BH

SPEAR BILL - BC

STEWART KARREN DIMMITT - BH

STRATTON BOB - BH

SWEENEY MARK - BC

SULLIVAN HEATHER LIVERGOOD - BH

SULLIVAN RAELENE ROGERS - BC

SULLIVAN RAYMOND J - BH

TATE WANDA DOTO - BH

THEREAULT VIVIGNNE HAACKE - BH

THOMAS FRANK - BC

THOMAS NANCY FOOTE - BC

TRAVIS BRUCE - BH

TREVENA MARILYN LUTZ - BH

TREVITHICK R J - BH

UELAND RAY - BC

UGRIN GARY - BC

VINE CAL - BH

VOLSKY GEORGE - BH

WARNER JOE - BH

WATTULA GAY DAILY - BH

WILLIAMS JOANI - BH

WILSON, GLADYS RAUH - BH

WITT MOLLIE VAUGHN - BH

WOLAHAN LINDA - BC

WOOLSEY ALINE TRIPLETT - BC

WORCESTER, CAROL CAVANAUGH- BH

WRIGHT WILMA IMMONEN - BH

ZOLYNSKI JAMES - BH