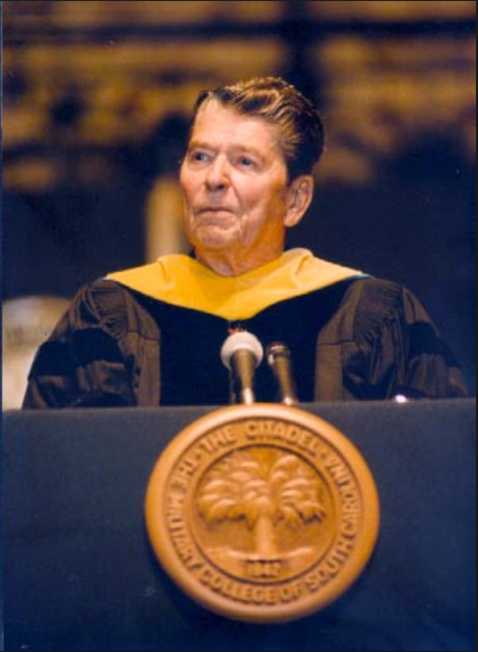

Commencement Address

The text of the speech by President Reagan, delivered on the occasion of our commencement. The original video, as it aired on C-Span can be found here.

OFFICE OF RONALD REAGAN

ADDRESS BY RONALD WILSON REAGAN,

40TH PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

AT THE 1993 COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES OF THE CITADEL

Charleston, South Carolina

McAlister Field House, The Citadel

Saturday, May 15, 1993

Embargoed for release upon delivery.

approximately 9:30 a.m. local time.

Check against delivery

###

REMARKS BY PRESIDENT RONALD REAGAN AT THE CITADEL

CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA

SATURDAY, MAY 15, 1993

I'm delighted to be here on this glorious day of hope and promise. It is indeed an honor to have the privledge of speaking to you today and to receive an honorary degree from this distinguished institution.

Surely my service record alone can't explain my presence here. More than half a century ago I was made a 2nd Lieutenant in the Horse Cavalry Reserve. That's hardly enough to warrant the honor you do me today.

But I do have to confess to you that during my presidency, I had an idea that I could never get anyone to support -- I wanted to reinstate the Horse Cavalry in the armed services.

Frankly, my being here cannot be based on my academic achievements either. Yes it's true that my alma mater -- Eureka College -- awarded me an honorary degree 25 years after my graduation. That one only aggravated a sense of guilt I'd nursed for 25 years. I've always suspected the first degree they gave me was honorary. Truthfully, I am very proud to receive this degree today and my prayer i sthat I can somehow be deserving of it.

It is a special pleasure to address the graduating class of 1993, as together we mark the culmination of The Citadel's sesquicentennial year. My goodness -- one hundred and fifty years. Has it really been that long? It seems like only yesterday that Colonel Harvey Dick and I were watching the first 20 members of the Corps of Cadets report for duty.

You know, the military college had been created that past December, and we weren't quite sure how things would turn out. I remember asking him, "Colonel Dick, do you think these 'original knobs' will make the grade?" Well, a week later, ten of them were serving "confinements", the other ten were finishing up "tours", and all 20 had turned in at least one "E.R.W." You see, some things never change. Come to think of it, I seem to recall the Colonel was even driving the same station wagon around Charleston. The only difference was that back then, that wagon had real horsepower.

Seriously, on my way to Charleston I took a peek at "The Guidon", which they tell me is the "Bible of the Knobs." The more I read that little booklet, the better I like it. For example, I learned the three permissable "knob answers": "Sir, yes sir", and "Sir, no sir" and -- I liked this third one best of all -- "Sir, no excuse, sir." By golly, I think we ought to send the entire U.S. Congress down here to learn answer number three.

Then I read this friendly advice in the book: "When you receive an order, carry it out to the best of your ability. Never argue or offer suggestions which you think might be better. This is not in your best interest." Well, it seems to me that The Citadel has a few things to teach the Cabinet and Executive Branch, too! In fact, maybe we should just put the whole Federal Government through cadet training!

But then I remembered that the last time the Corps of Cadets and good people of Charleston decided the Federal Government was taking too active an interest in their affairs. Before you knew it, Cadet George Haynsworth and the other "Boys Behind the Gun" had fired the famous "first shot" at the Yankee steamer "Star of the West." Well we all know what happened after that. As I recall, it took a good four years before everything calmed down again. Just think of the "E.R.W." those fellas would have had to write!

In fact, of course, the "Boys Behind the Gun" served valiantly the cause to which they had pledged their devotion. In this, they exemplified a Citadel tradition -- a tradition that would transcend the divisions of our nation's bloodiest internal struggle, and inspire generations of future cadets to courageous service to a nation reunited.

The Citadel's roll of honor today stretches unblemished from the Ardannes to the 38th Parallel, from Grenada to the Persian Gulf, with name after name of those who have served our country bravely in time of war -- names like General Charles Summerall, General Mark Clark, and your current President, General Bud Watts. Yes, countless soldiers have distinguished themselves on fields of valor and are part of the century-and-a-half tradition of duty and honor we celebrate today.

But for me, there is one name that will always come to mind whenever I think of The Citadel and the Corps of Cadets. It is a name that appears in no military histories; its owner won no glory on the field of battle.

No, his moment of truth came not in combat, but on a snow-driven, peacetime day in the Nation's capital in January of 1982. That is the day that the civilian airliner, on which he was a passenger, crashed into a Washington bridge, then plunged into the rough waters of the icy Potomac. He survived the impact of the crash and found himself with a small group of other survivors struggling to stay afloat in the near-frozen river. And then, suddenly, there was hope: a park police helicopter appeared overhead, trailing a lifeline to the outstretched hands below, a lifeline that could carry but a few of the victims to the safety of the shore. News cameramen, watching helplessly, recorded the scene as the man in the water repeatedly handed the rope to the others, refusing to save himself until the first one, then two, then three and four, and finally five of his fellow passengers had been rescued.

But when the helicopter returned for one final trip, the trip that would rescue the man who had passed the rope, it was too late. He had slipped at last beneath the waves with the sinking wreckage -- the only one of 79 fatalities in the disaster who lost his life after the accident itself.

For months thereafter, we knew him only as the "unknown hero." And then an exhaustive Coast Guard investigation conclusively established his identity. Many of you here today know his name as well as I do, for his portrait now hands with honor -- as it indeed should -- on this very campus: the campus where he once walked, as you have, through the Summerall Gate and along the Avenue of Rememberance. He was a young first classman with a crisp uniform and a confident stride on a spring morning, full of hopes and plans for the future. He never dreamed that his life's supreme challenge would come in its final moments, some 25 years later, adrift in the bone-chilling waters of an ice-strewn river and surrounded by others who desperately needed help.

But when the challenge came, he was ready. His name was Arland D. Williams, Jr. The Citadel Class of 1957. He brought honor to his alma mater, and honor to his nation. I was never more proud as President than on that day in June 1983 when his parents and his children joined me in the Oval Office -- for then I was able, on behalf of the nation, to pay posthumous honor to him. Greater love, as the Bible tells us, hath no man than to lay down his life for a friend.

I have spoken of Arland Williams in part to honor him anew in your presence, here at this special institution that helped mold his character. It is the same institution that has now put its final imprint on you, the graduating seniors of its 150th year. But I have also retold his story because I believe it has something important to teach you as graduates about the challenges that life inevitably seems to present -- and about what it is that prepares us to meet them.

Sometimes, you see, life gives us what we think is fair warning of the choices that will shape our future. On such occasions, we are able to look far along the path, up ahead to that distant point in the woods where the poet's "two roads" diverge. And then, if we are wise, we will take time to think and reflect before choosing which road to take before the junction is reached.

But such occasions, in fact, are rather rare -- far rarer, I suspect, than the confident eyes of one's early twenties can quite perceive. Far more often than we can comfortably admit, the most crucial of life's moments come like the scriptural "thief in the night." Suddenly and without notice, the crisis is upon us and the moment of choice is at hand -- a moment fraught with import for ourselves, and for all who are depending on the choice we make. We find ourselves, if you will, plunged without warning into the icy water, where the currents of moral consequence run swift and deep, and where our fellow man -- and yes, I believe our Maker -- are waiting to see whether we will pass the rope.

These are not the moments when instinct and character take command, as they took command for Arland Williams on the day our Lord would call him home. For there is no time, at such moments, for anything but fortitude and integrity. Debate and reflection are a leisurely weighing of the alternatives and luxuries we do not have. The only question is what kind of responsibility will come to the fore.

And now we come to the heart of the matter, to the core lesson taught by the heroism of Arland Williams on January 13, 1982. For you see, the character that takes command in moments of crucial choices has already been determined.

It has been determined by a thousand other choices made earlier in seemingly unimportant moments. It has been determined by all the "little" choices of years past -- by all those times when the voice of conscience was at war with the voice of temptation -- whispering the lie that "it really doesn't matter." It has been determined by all the day-to-day decisions made when life seemed easy and crises seemed far away -- the decisions that, piece by piece, bit by bit, developed habits of discipline or of laziness; habits of self-sacrifice or self-indulgence; habits of duty and honor and integrity -- or dishonor and shame.

Because when life does get tough, and the crisis is undeniably at hand -- when we must, in an instant, look inward for strength of character to see us through -- we will find nothing inside ourselves that we have not already put there.

And you know, it turns out that much the same thing is also true for our country. Indeed, I believe that this is especially so in the most crucial area of all -- America's ability, when necessary, to defend her citizens and her freedoms and her vital interests by force of arms. For here, too, the crisis is often upon us in an instant. Here, too, our instincts and character must be equal to challenges we can scarcely predict. But here, even character and instinct will not be enough. We must also have the tools -- the military capability -- ready in advance of the crisis that may demand their use.