The following provides an extract from the book "Brokie's Way: An anthropologists story" which is available online at www.brokiesway.co.za/youth.htm

David Brokensha was in the class of 1939, and has been invited onto this website as a Guest.

If you wish to be in touch with him just click on his name in Classmate Profiles.

SCHOOLS

Many memoirs, especially if written by boys who attended boarding schools, contain an almost obligatory account of hated and miserable schooldays, often featuring sadistic teachers and bullying boys. I was fortunate in that I loved school right from the start. I had no experience of being a boarder, and I remember few unhappy times.

I recall the excitement of my first day at school: Miss MacColl’s kindergarten on Montpelier Road. The school was located in Miss MacColl’s house, where each weekday about a dozen little boys and girls walked up the whitewashed steps to begin their first lessons. One of my few surviving school reports – from 1930, when I was six or seven – notes, in Miss MacColl’s careful handwriting: Singing: Not much ear but he tries. Unfortunately, despite my appreciation of others’ singing, I have never developed a remotely acceptable voice. Miss MacColl softened the blow by adding I am sorry to lose an interesting and conscientious pupil.

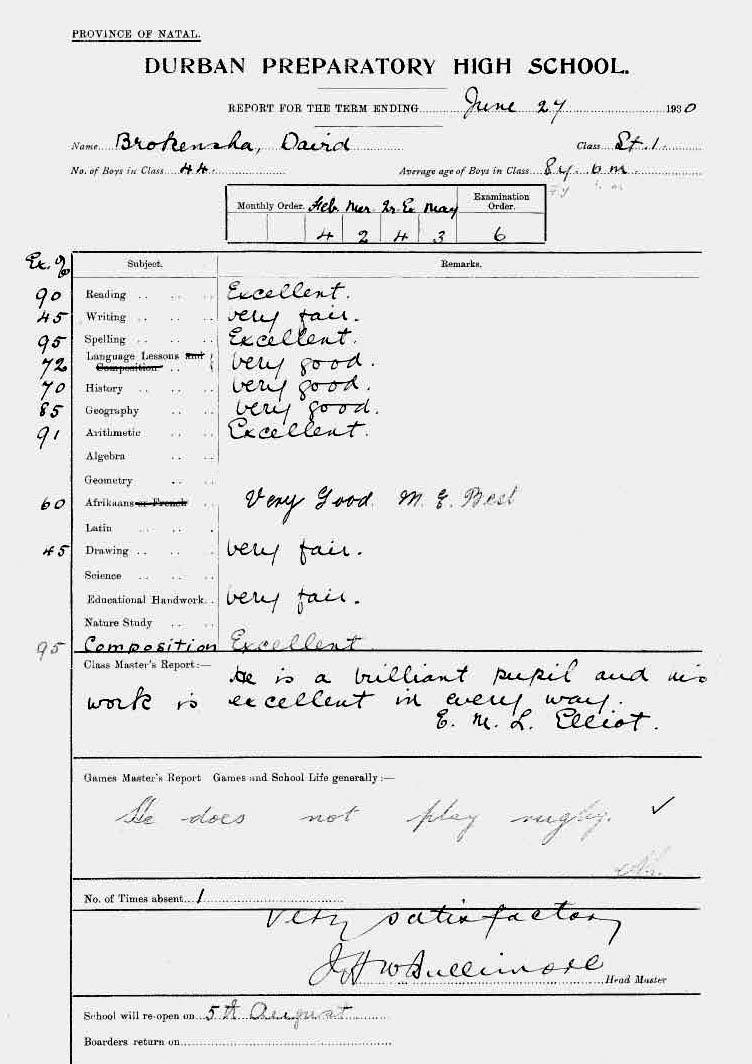

Ouma and Dad showed pleasure and pride when we got good school reports. Another report, written when I was in Standard IIA, at the ‘Prep’ ( Durban Preparatory High School) in 1931, states: David is a very intelligent pupil and can do excellent work when he is not too ‘dreamy’. I confess, not with pride but with embarrassment, that I remain ‘dreamy’ right up to the present, a trait which frequently puzzled and occasionally irritated Bernard. This same report rates me ‘fair’ for woodwork, which is far too kind: I was hopeless at woodwork, and while some little master carpenter next to me was making a perfect mortise and tenon, I would be struggling with a shapeless chunk of wood.

I do not recall any help with homework: we expected to do that on our own, seeking advice, if needed, from our school pals, not from our parents. There were no Parent–Teacher Associations, and schoolteachers discouraged too close an interest by parents in the day-to-day operations of the school. Parents were encouraged to come only on formal occasions, such as to rugby or cricket matches against rival schools, or to plays. During my five years at Durban High School, I doubt whether my parents came to the school more than once or twice a year.

Guy, Paul and I all attended, at various times, Durban Preparatory High School and Durban High School (DHS), as day-boys. Relatively few memories surface of my time at the Prep: games of marbles, spinning tops, or tinto (placing five or six peach stones on the back of one’s hand, tossing them in the air and catching as many of them as possible), though I seldom excelled in these games. When we lived in Eleventh Avenue, Fanyan sometimes brought Paul and me our lunch at the Prep, which was less than a mile from home. Accompanied by Punch – who was as pleased to see me as I was to see him – Fanyan came with a Red Riding Hood type of basket, covered by a neat white cloth, with our lunches carefully prepared by Ouma. Then it was time for school again, and ‘Goodbye Fanyan; goodbye Punch.’

I remember Miss Bull, a formidable new teacher, storming into our classroom, announcing, ‘I’m bull by name and bull by nature, so don’t give me any trouble.’ Some time later, one of the bolder – or more imaginative – boys told us that he had gone to the staffroom and, finding no teacher present, had looked inside Miss Bull’s handbag, ‘and do you know what I saw? … there was a revolver and a French letter.’ This dramatic announcement stuck in my memory, representing the acme of wickedness – even though I had to ask Paul what a ‘French letter’ was, and his explanation left me puzzled.

I admired my father for never indicating that he was disappointed at my lack of interest, or skill, in rugby and cricket. Despite being optimistically described in my Standard IV school report as ‘a dependable forward’, I was incompetent at team sports. More than sixty years later, I still clearly remember the disgust in Mr Loock’s voice after I had dropped the ball for the umpteenth time: ‘Brokie,’ – pause – ‘you can’t be a Brokie; not the way you play rugby.’

On the cricket field, I fared no better. Young twelve-year-old Don Bradmans took it in turn to select their teams from among their schoolmates. At the end, when I was the only boy left unselected, one of the captains would say, disconsolately, ‘Oh well, I suppose I’ll have to take Brokie.’ I can understand their reluctance. I was put at long-stop, on the edge of the field, where I would day-dream happily until there was a shout of ‘Brokie! Come on, Brokie! Wake up!’ Too late: the ball had rolled way past me. Then there was the ignominy of having to throw the ball back, and all I could manage was a feeble few yards. More groans. When I told Bernard this story, many years later, he thought that I must have been scarred by this treatment: I do not think so; I was self-sufficient in my own world, with my few good chums – I did not need the approval of those whom WH Auden famously referred to as ‘muddied oafs and flannelled fools’. Fortunately I was a good swimmer, which somewhat saved my reputation.

An early school report

As for the school Cadet Corps, I loathed the whole exercise and managed to get myself excused – I do not remember on what grounds. Instead of the pointless marching up and down, I helped two disabled boys hand out rifles and uniforms.

Guy attended DHS under the legendary headmastership of Mr Langley, who was obsessed with working out what had ‘really happened’ at the Battle of Waterloo. From the lawn outside his study, Mr Langley overlooked the playing fields twelve feet below. Guy told me that at least once a year, whistles would blow, and all three hundred and fifty boys would assemble on the playing fields, in their respective classes, each representing one of the warring battalions, with the headmaster directing the battle from above. Mr Langley would call out: ‘No, Blücher must have been further to the west … move over, Form IVAs …’

The form masters were angry at having their lessons interrupted, but everyone accepted Mr Langley’s obsession. What a wonderful way of playing soldiers! Surely this was better than being obsessed, as other headmasters were, with ‘immorality’. Guy told me that as a result of these unscheduled exercises he had a good understanding of why the Duke of Wellington had said that he nearly lost the Battle of Waterloo. Although they brought history vividly alive, such unorthodox methods – involving the whole school – would probably be frowned on today.

I was caned twice during my time at DHS, the first occasion being on my very first day at school. Proudly wearing my new boater (the school straw hat, commonly referred to as a ‘basher’), I walked under an arch, and was promptly told by one of the school prefects to follow him. I knew this senior boy – everyone knew Skonk Nicholson (head boy, captain of both cricket and rugby) – and I wondered why he should deign to notice me. Taking me into the ‘boot room’, where several other prefects lounged about, he told me to bend over, and, with no explanation, he caned me. It was not very painful: I remember feeling above all puzzled as to what my offence was. As I left the room, one of the prefects said, ‘Next time, you will pay respect and remove your basher.’ Later I learned that the arch was a memorial to DHS boys who had been killed in World War 1. Lesson learnt.

One morning a few years later, Alastair Dark and I were cycling along Currie Road on our way to school, and blithely rode across Sydenham Road, as we did each morning. But we had ignored a newly-installed STOP sign, and were called over by a police officer who must have been lying in wait. He said that it was no good charging us, so instead he would report us to our headmaster, who would mete out our punishment. Mr Black felt obliged to give us a lecture on road safety, followed by a perfunctory caning. Neither caning did me any harm, in fact, for a usually obedient boy, the canings increased my school ‘cred’.

Mr Langley’s successor, Mr Black, also had an obsession, but of a much more mundane sort: he could not abide boys smoking cigarettes. On one memorable occasion the entire cricket First XI was discovered smoking. At assembly the following morning the whole school was present (including the Jewish boys, normally excused from prayers) while the disgraced cricket team stood nervously on the platform with the headmaster and staff. After giving a short lecture on the evils of smoking, ‘which will not be tolerated in my school’, Mr Black proceeded to cane each of the cricketers, who had to bend over in turn to receive ‘six of the best’. Mr Black was so angry that he lost count, giving one boy only five strokes. This was followed by a shout from the floor: ‘You missed one, sir.’ We all burst out laughing.

Mr Black sailed, not very skilfully, on Durban Bay. We encountered him one Saturday, when Paul and I were in Jimmy Whittle’s twenty-two foot scow. Paul persuaded Jimmy to let him take over the helm and executed a deft manoeuvre, going sharply about, right in front of Mr Black’s craft, and showering him with a sheet of water. ‘Oh, sorry, sir,’ shouted a joyful Paul, while Mr Black glowered at one of his most unruly and impudent pupils.

I am grateful to most of my schoolmasters, particularly to Neville Nuttall, who taught us English, which he loved. He enlarged my horizons, leading me to an appreciation of English literature. I was assistant editor of the school magazine, and also secretary of the Debating Society, both of these positions supervised by Mr Nuttall. The main purpose of the Debating Society was to introduce outside speakers, and I was given a free hand in inviting these guests. Once, when I was stuck for a speaker, I enlisted my father’s cousin, Leslie Brokensha, who used to write as The Wayfarer in the Natal Daily News. On another occasion I invited my Auntie Lil’s husband, Sidney Brisker, then a senator for the governing United Party. Both Leslie and Sidney were flamboyant characters, and both did me proud, as did Jock Leyden, cartoonist on the Natal Mercury, who delighted us with his rapid sketches and insightful comments. My involvement in these activities marked the beginning of my awareness of the grave political, social and environmental problems facing South Africa, and of the huge inequalities in its society. In these extramural activities Neville Nuttall was always there, unobtrusively encouraging and guiding me.

On one occasion I arranged for the Sixth Form to visit the Durban abattoir, where we witnessed the ‘Judas goat’ leading the hapless sheep up to the slaughter house. I was most proud of having also organised a tour, by train, of about twenty of my school mates, to Johannesburg, Pretoria and Kimberley. The South African Railways staff were most accommodating – once they had recovered from their shock at dealing with a young boy. On this tour, members of the Old Boys Association kindly took us into their homes, and arranged for us to visit places of interest. It was my first visit to the Transvaal and to the Northern Cape.

In 1938 my Uncle Sidney was invited to open the new Cameo cinema, built on the site of a garage. Our grandest cinema, the Playhouse, had recently been opened, marked by the dramatic ascent – presumably by hydraulic lift – of the entire pit, with the orchestra conducted by Charles Manning, known locally as ‘the Svengali of music’. The management of the Cameo foolishly tried to emulate the Playhouse, and placed a small band, plus Uncle Sidney, on what had been the garage’s hydraulic lift. Instead of moving upwards majestically, the lift jerked, causing Uncle Sidney and the band to lurch about precariously. Uncle Sidney giggled, and I realised that he was tipsy. I had invited a few school friends to the ceremony, boasting about my uncle, and I was afraid that he was about to embarrass me. But, despite his imbibing, he gave a good, clear speech, and I was saved. Uncle Sidney sometimes invited me, aged fifteen, to lunch at his club, where he treated me like an adult, offering me a sherry, and asking me about my school activities: I was thrilled, and encouraged.

In the junior forms, history lessons concentrated on South Africa, with emphasis on dramatic episodes such as the Great Trek of the 1830s, when many Afrikaner families left the Cape Colony to settle in the interior, partly in protest against the emancipation of slaves. The history syllabus inevitably focused on the whites, with the few Africans who were mentioned being shadowy figures – obedient servants, or violent enemies.

Mr Evans, our history master, had firm ideas about teaching: for example, when we were studying the French Revolution we learnt the Seven Causes, the Seven Courses and the Seven Effects – hardly any of which can I recall today. Mr Evans was demanding, requiring the upper forms to write an essay every week. When I arrived home on Friday afternoons, Ouma would urge me to write the essay and get it out of the way, but often I was distracted by friends, and then on Saturday and Sunday I would spend all day on the bay, or at the beach, and would be too tired in the evening to tackle the essay. The result was that I would get up on Monday morning at 4 a.m. and write desperately. Later in my life I have had occasion to resort to this tactic, finding that the early hours are my most productive.

Durban Library had an excellent children’s section headed by Mrs Barnes (whose niece, Jil, later married my brother Paul). I was a keen reader, and was encouraged by Mrs Barnes, who would set aside the latest of my current favourites – the Tarzan, Just William or Doctor Dolittle books – then gently suggest that I also take out ‘this’, and hand me a more challenging but not too daunting volume.

Looking back on my school years, I realise that we had many opportunities for acquiring a cultural education, and I took advantage of them. First there was the bio – the bioscope, as the cinema was then called. From an early age I loved to go to the old Empire Bio, where the first movies that I saw were silent. I couldn’t read fast enough to read the sub-titles: ‘ Guy, Guy,’ I would plead, ‘what are they saying?’ It was no good asking Paul, he would be too wrapped up in the drama, and his own reading skills were still limited. One of the first talking movies that we saw was Peter Pan, and when Peter Pan asked, ‘Do you believe in fairies?’ my childish treble rang out (so Paul later told me), ‘Oh, yeth, I do!’

In 1937 a local amateur ‘dram soc’ put on a production of Our Town, in which I played the newsboy. My part required me to speak only a few one-liners, but the director congratulated me on my ‘excellent performance’, continuing, ‘I hope that your interest in the theatre will be maintained.’ While loving the theatre, I soon realised that I was no actor, but I continued to help backstage, mainly as the call boy – ‘Two minutes please, Miss X’ – for plays produced by the Durban Jewish Guild or the Bachelor Girls or other lively local amateur dramatic societies.

I appeared on stage for one other role, that of Nerissa, Portia’s maid, in the 1939 DHS production of The Merchant of Venice. Michael Turner played Portia brilliantly, telling me, after the last performance, that he was going to be a professional actor. After serving five years in the South African Air Force in World War 2, he enrolled in a drama school in London. When I visited Oxford in 1966, I saw Michael’s name at the Oxford Playhouse, as a leading player in the National Theatre’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. We had a happy reunion, not having seen each other for twenty years.

Ouma encouraged my musical interests, taking me to the Carl Rosa Opera Company when they visited Durban. Edward Dunn, conductor of the Durban Symphony Orchestra, gave special Saturday morning performances for school children, in the Town Hall. Going through such pieces as Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, he gave us a lively introduction to the orchestra, and to orchestral music.

![]()