Irvington High School

Out Of Our Past - Alan Siegel

This page, continued from past newsletters, is updated on an ongoing basis - the most recent first. Each entry on this site is dated.

Out Of Our Past

Thirtieth in a series of excerpts from OUT OF OUR PAST

A history of Irvington, New Jersey by Alan Siegel—Copyright 1974

(Continued on July 28, 2014)

Rich or poor, young or old, nearly everyone in Irvington enjoyed the annual visit of Barnum and Bailey's Circus, an attraction on the Ollemar tract from about 1905 to 1912, and again from 1931 to 1943. In May 1912, the circus arrived in typical fashion, featuring a ballet of 350 dancing girls, a grand opera chorus, and an orchestra of 100. Six hundred and fifty horses, five herds of camels, 40 elephants, and a "trainload of special scenery, costumes, and stage mechanisms for producing such effect as sand storms on the desert, earthquakes, sunrises, mirages, thunder, lightning, and rain" were needed to perform that year's scenic spectacular, "Cleopatra," presented by a cast of 1,250. Drake & Co., which fed the animals, furnished six tons of hay, three tons of straw, 200 bushels of oats and 7,000 pounds of grain in one day.

The circus returned to Irvington again in September 1974, after an absence of 31 years, when the Irvington Centennial Committee sponsored two performances of the Hoxie Bros. Circus at Chancellor Playground.

The Ollemar tract, first used for athletic events in 1895, played host to a wide variety of sports activities before the Parkway Apartments were built after World War II. Jack Johnson, the former heavyweight boxing champion, wrestled there at the age of 60. Satchel Paige, the ageless wonder, repartedly clouted a baseball over the fence into the windows of the Olympic Restaurant.

Out Of Our Past

Twenty-ninth in a series of excerpts from OUT OF OUR PAST

A history of Irvington, New Jersey by Alan Siegel—Copyright 1974

(Continued on April 30, 2014)

When Olympic Park closed its gates for the last time in the fall of 1965, it marked the end of an era. The park was a part of growing up in Irvington for over 60 years, and rare indeed was the youngster who never visited the amusement center, not just once but many times. Ball games on the corner lot, the circus at Ollemar Field, and Tri-City Stadium races were just a few of the other ways Irvingtonians spent their leisure time.

It was not so many years ago that long weekends and summer vacations were exclusively the province of the rich. Leisure time, what precious little there was of it, was spent on simple amusement close to home. Church strawberry festivals at a nearby grove, or trolley rides to the Big Tree in Belleville with the family on Sunday were pleasure enough for the man or woman who worked 52 weeks a year, six days a week, 12 to 14 hours a day. Organized recreation, such as George Wooley's dancing parlor on Ball Street which opened in 1889, or the rink at the corner of Springfield Avenue and Lake Street where minstrel shows held forth, were rare in an era when many still equated leisure with idleness and called it the work of the devil.

Clifford Sippell, who grew up in Irvington during the 1890s, remembered how eagerly they awaited the annual visit of the Kickapoo Indian medicine show on the ball grounds at Clinton Avenue and Smith Street. The promoter and the banjoist and comedian entertained the crowd until the feature attraction, "real" Kickapoo Indians in native dress and grease paint, whooped onto the stage, startling the youngsters with their fierce dances and wild war cries.

For the men of the village, Irvington's many neighborhood saloons, equipped with penny slot machines, free lunches, and good companionship, were favorite places to relax. Among the most popular at the turn of the century were Francis Schaefer's Park and Hotel at the corner of Union and Lyons avenues, renowned for its outdoor suppers in the wooded grove; Kilian Jubert's tavern at 1347 Springfield Avenue, famous for its all-night dinner parties; Hosp's Hotel at 43rd Street and Springfield Avenue, which catered to Olympic Park visitors; and a host of others, including Pape's, Wiedenbacher's, Rechsteiner's, Bader's and Bonscher's on the Speedway.

* * * * * * * * * *

Out Of Our Past

Twenty-eighth in a series of excerpts from OUT OF OUR PAST

A history of Irvington, New Jersey by Alan Siegel—Copyright 1974

(Continued on January 30, 2014)

It was early on the morning of April 12, 1912, when the first copies of The Clinton Weekly, newest entry in a long list of short-lived Irvington newspapers, were rushed by bicycle to several hundred curious townspeople. For two anxious young men, one of them a minister, the other a transplanted New Englander, the eight-page journal represented more than months of planning and hard work. At stake was their dream that Irvington could sustain a quality weekly dedicated—in their words—to a "knowledge of what is worth knowing, and what is worth doing, and what is worth supporting."

Today (1974) the Irvington Herald, successor to The Clinton Weekly, carries on in the spirit of Walter S. Gray and the Rev. Uriah McClinchie.

After more than 3,200 editions, the philosophy of the co-founders, expressed on the first page of Vol. 1, No. 1, still stands behind the newspaper: "I believe that the place in which I live while I live in it, it for me the best place in all the world, and that as it gives to me the best it has, it deserves from me in return the best I can give it."

Out Of Our Past

Twenty-eighth in a series of excerpts from OUT OF OUR PAST

A history of Irvington, New Jersey by Alan Siegel—Copyright 1974

(Continued on September 30, 2013)

YOU DON'T NEED AN EXCUSE TO BUY A LIONEL

In the distance, a New York Central locomotive puffing smoke rounds a curve, trailing a string of brightly-lit passenger cars. Nearby, in the middle of a busy freight yard, a diesel engine moves cautiously past a flashing green semaphore, halting alongside a row of unloading platforms. At a signal, flatcars dump wooden logs onto a conveyor; a worker rolls milk cans from a refrigerated car; and cattle, more than a score of them, file silently into pens from a boxcar. Round a mountain crowned with trees and into a dark tunnel roars a Santa Fe engine, its whistle blaring an impatient warning that echoes across a nearby town. At the passenger station, meanwhile, a trainmaster waits, watch in hand, for the 6:05 to steam around the south bend.

Years ago that was a scene which to millions of American families meant only one thing—Christmas! Soon after the cards were mailed, and days before the Christmas tree was selected from a lot down the street, the model trains were unpacked and set up in a corner of the living room. "You don't need a son as an excuse to buy a Lionel train," the ads proclaimed. The electric train and all its amazing paraphernalia were a holiday tradition for "boys of all ages" that during its heyday, from 1910 to 1955, was the nation's single most popular toy.

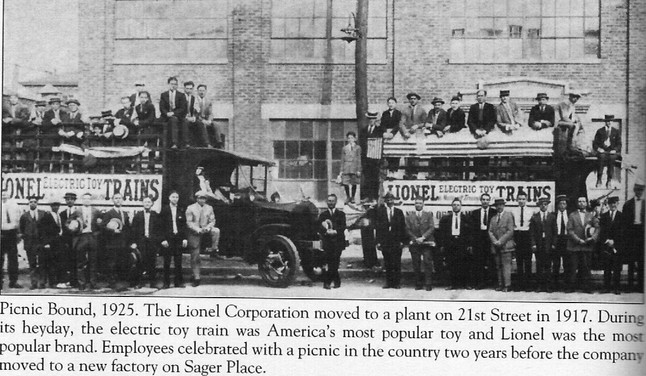

Dominating the American market for many of those years was the Lionel Corp., located on Sager Place. From 1917, when Lionel moved to Irvington from Newark, until 1967, when the corporation relocated its factory in Maryland, Lionel was one of Irvington's largest industries, and certainly the best-known. Over the years, thousands of Irvingtonians worked at the plant, crafting the trains, track, and accessories that made Lionel the leader in its field, and for many years the world's largest manufacturer of toy electric trains.

Lionel came to Irvington in 1917, employing nearly 700 people in a small plant on South 21st Street. Later, needing even more space, Lionel constructed a huge factory on Sager Place, to which it oved in 1926. During World War I, Lionel shifted from trains to war materials, producing precision compasses, binnacles, periscopes, and navigation aides for the Navy Department. With the return of peace came prosperity, and with it the model train market entered its greatest period. By 1921, more than one million Lionel train sets had been sold.

World War II forced a second interruption in Lionel's toy manufacture when production lines were converted to more than 100 different defense products. Lionel resumed normal operations in 1945, mass-producing train sets and accessories that on e again captured the nation's fancy. By 1950, one of Lionel's best years, 2,000 people worked in the Sager Place plant, over two-thirds of them residents of Irvington. With its long-remembered Golden Jubilee line of 1950, Lionel introduced Magne-Traction, a 26-inch bridge modeled on Newark's Stickel Bridge, and ahost of even more realistic accessories.

The Lionel Corp. fell on hard times in the late fifties and early sixties. Soon after Joshua Cowen died, the company came under new management. Labor problems, a sharp decline in sales, and internal corporate unrest climaxed in 1967 when Lionel closed its plant and headed south to Maryland, bringing to an end a memorable half-century of toy making in Irvington.

Out Of Our Past

Twenty-seventh in a series of excerpts from OUT OF OUR PAST

A history of Irvington, New Jersey by Alan Siegel—Copyright 1974

(Continued on July 20, 2013)

THE WONDER OF THE TOWN

After the Wright Brothers accomplished mankind's first powered flight in December 1903, literally hundreds of flying machines were constructed. Scores became airborne, ifonly in a faltering sort of way. The few that performed reasonably well encouraged others, and each year the excitement grew. Irvington's only entry in the great race to conquer the sky began to take form in November 1911, when Fred. M.A. Rudolph of Irvington and Frank Brown of Newark founded the Rudolph Aeroplane Co. In rented quarters at the rear of the Zigenfus Brothers garage at 960 Springfield Avenue, they constructed a six-passenger monoplane that became the wonder of the town. Of all the business firms ever located in Irvington, the Rudolph Co. was the only one that ever built an airplane.

According to the Clinton Weekly, the Rudolph airplane resembled a "huge cross." Measuring 65 feet from wing tip to wing tip, 37 feet from head to tail, and eight feet in height, it was driven by two propellors connected to a 90-horsepower engine. Carrying 60 gallons of gasoline, the monoplane could fly continuously for 18 hours at an average speed of 50 mph. "The monoplane is built for safety, not speed," explained the newspaper.

Although finished in late July, the airplane still remained grounded. "The huge monoplane built by Rudolph Aeroplane Co. is now on exhibition at the veledrome in Vailsburg," the Clinton Weekly reported. "If permission can be obtained from the Essex County Park Commission, it is possible the flight may take place in Irvington Park. Failing this, the machine will be taken to Summit for a trial."

Rudolph and Bowers' great dream turned to ashes in the fall of 1912. Evicted by Zigenfus for nonpayment of rent, the Rudolph Aeroplane Co. was finished. Its huge monoplane, which never actually became airborne, was sold at public auction for $5 and carted away as scrap.

Out Of Our Past

Twenty-seventh in a series of excerpts from OUT OF OUR PAST

A history of Irvington, New Jersey by Alan Siegel—Copyright 1974

(Continued in April, 2013)

Irvington Centre - 1939

Out Of Our Past

Twenty-sixth in a series of excerpts from OUT OF OUR PAST

A history of Irvington, New Jersey by Alan Siegel—Copyright 1974

(Continuing from past issues of The Torch - March 2013)

"The work of harvesting the first crop of ice to be gathered from the Irvington ponds was begun Tuesday morning, and late that night half an acre of fine ice had been take from each of the two ponds which were being operated. The ice men were encouraged over this outlook, and expected they would have the crops in before the weather changed.

"Until a few days ago the ice men feared that they would not harvest any ice this season, on account of the uncertain weather. Several times this winter, when the ice had been of sufficient thickness to admit cutting, a rain or a thaw would set in and spoil their hopes.

"At the Seiler brothers pond on Springfield Avenue, a large gang of men were set to work Tuesday morning. The ice was from seven to nine inches in thickness and was as clear as crystal.

"For some unknown reason, the ice always freezes much faster on Drake's upper pond than an other of the Irvington ponds, and Mahlon Drake, the owner, was superintending the housing of ice, which was from nine to twelve inches in thickness. Mr. Drake is certain of harvesting the crop, for if a thaw sets in he is prepared to put a gang of men at work nights until the commodity is safely housed.

"Ice will be high in this vicinity next summer, and the ice on the Irvington ponds represents a considerable amount of money. It is also a boon to local workmen who have found employment on the ponds. The work of harvesting the ice on Drake's two other ponds will be begun in a few days.

"Matthias D. Dorer, of Stuyvesant Avenue, has filled his house with about 100 tons of ice, which is to be used by him. Only a few years ago Mr. Dorer conceived the idea of erecting a house and cutting ice which was formed in a small pond at the rear of his property. As he is a large consumer of this commodity, it is cheaper for him to cut his own ice than to buy from the dealers."

Irvington's growth doomed the ice business. When the last ice house at Drake's Lower Pond was destroyed by fire in 1913, it marked the end of an era.