Irvington High School

Reminiscing

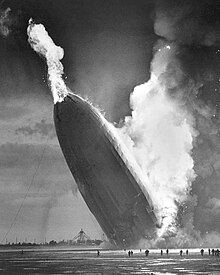

THE HINDENBURG DISASTER

After opening its 1937 season by completing a single round-trip passage to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in late March, the Hindenburg departed from Frankfurt, Germany, on the evening of May 3, on the first of 10 round trips between Europe and the United States that were scheduled for its second year of commercial service. American Airlines had contracted with the operators of the Hindenburg to shuttle the passengers from Lakehurst to Newark for connections to airplane flights.[3]

Except for strong headwinds that slowed its progress, the Atlantic crossing of the Hindenburg was otherwise unremarkable until the airship attempted an early-evening landing at Lakehurst three days later on May 6. Although carrying only half its full capacity of passengers (36 of 70) and crewmen (61, including 21 crewman trainees) for the accident flight, the Hindenburg was fully booked for its return flight. Many of the passengers with tickets to Germany were planning to attend the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in London the following week.

The Hindenburg over Manhattan, New York on May 6, 1937, shortly before the disaster

The airship was hours behind schedule when it passed over Boston on the morning of May 6, and its landing at Lakehurst was expected to be further delayed because of afternoon thunderstorms. Advised of the poor weather conditions at Lakehurst, Captain Max Pruss charted a course over Manhattan Island, causing a public spectacle as people rushed out into the street to catch sight of the airship. After passing over the field at 4:00 p.m., Captain Pruss took passengers on a tour over the seasides of New Jersey while waiting for the weather to clear. After finally being notified at 6:22 p.m. that the storms had passed, Pruss directed the airship back to Lakehurst to make its landing almost half a day late. However, as this would leave much less time than anticipated to service and prepare the airship for its scheduled departure back to Europe, the public was informed that they would not be permitted at the mooring location or be able to visit aboard the Hindenburg during its stay in port.

Around 7:00 p.m. local time, at an altitude of 650 feet (200 m), the Hindenburg made its final approach to the Lakehurst Naval Air Station. This was to be a high landing, known as a flying moor, because the airship would drop its landing ropes and mooring cable at a high altitude, and then be winched down to the mooring mast. This type of landing maneuver would reduce the number of ground crewmen, but would require more time. Although the high landing was a common procedure for American airships, the Hindenburg had only performed this maneuver a few times in 1936 while landing in Lakehurst.

At 7:09, the airship made a sharp full-speed left turn to the west around the landing field because the ground crew was not ready. At 7:11, it turned back toward the landing field and valved gas. All engines idled ahead and the airship began to slow. Captain Pruss ordered aft engines full astern at 7:14 while at an altitude of 394 ft (120 m), to try to brake the airship.

At 7:17, the wind shifted direction from east to southwest, and Captain Pruss ordered a second sharp turn starboard, making an s-shaped flightpath towards the mooring mast. At 7:18, as the final turn progressed, Pruss ordered 300, 300 and 500 kg of water ballast in successive drops because the airship was stern-heavy. The forward gas cells were also valved. As these measures failed to bring the ship in trim, six men (three of whom were killed in the accident)[Note 1] were then sent to the bow to trim the airship.

At 7:21, while the Hindenburg was at an altitude of 295 ft (90 m), the mooring lines were dropped from the bow; the starboard line was dropped first, followed by the port line. The port line was overtightened as it was connected to the post of the ground winch. The starboard line had still not been connected. A light rain began to fall as the ground crew grabbed the mooring lines.

At 7:25 p.m., a few witnesses saw the fabric ahead of the upper fin flutter as if gas were leaking.[4] Others reported seeing a dim blue flame – possibly static electricity, or St Elmo's Fire – moments before the fire on top and in the back of the ship near the point where the flames first appeared.[5] Several other eyewitness testimonies suggest that the first flame appeared on the port side just ahead of the port fin, and was followed by flames which burned on top. Commander Rosendahl testified to the flames in front of the upper fin being "mushroom-shaped". One witness on the starboard side reported a fire beginning lower and behind the rudder on that side. On board, people heard a muffled detonation and those in the front of the ship felt a shock as the port trail rope overtightened; the officers in the control car initially thought the shock was caused by a broken rope.

Hindenburg begins to fall seconds after catching fire

At 7:25 p.m. local time, the Hindenburg caught fire and quickly became engulfed in flames. Eyewitness statements disagree as to where the fire initially broke out; several witnesses on the port side saw yellow-red flames first jump forward of the top fin near the ventilation shaft of cells 4 and 5.[4] Other witnesses on the port side noted the fire actually began just ahead of the horizontal port fin, only then followed by flames in front of the upper fin. One, with views of the starboard side, saw flames beginning lower and farther aft, near cell 1 behind the rudders. Inside the airship, helmsman Helmut Lau, who was stationed in the lower fin, testified hearing a muffled detonation and looked up to see a bright reflection on the front bulkhead of gas cell 4, which "suddenly disappeared by the heat". As other gas cells started to catch fire, the fire spread more to the starboard side and the ship dropped rapidly. Although there were cameramen from four newsreel teams and at least one spectator known to be filming the landing, as well as numerous photographers at the scene, no known footage or photograph exists of the moment the fire started.

Wherever they started, the flames quickly spread forward first consuming cells 1 to 9, and the rear end of the structure imploded. Almost instantly, two tanks (it is disputed whether they contained water or fuel) burst out of the hull as a result of the shock of the blast. Buoyancy was lost on the stern of the ship, and the bow lurched upwards while the ship's back broke; the falling stern stayed in trim.

As the tail of the Hindenburg crashed into the ground, a burst of flame came out of the nose, killing 9 of the 12 crew members in the bow. There was still gas in the bow section of the ship, so it continued to point upward as the stern collapsed down. The cell behind the passenger decks ignited as the side collapsed inward, and the scarlet lettering reading "Hindenburg" was erased by flames as the bow descended. The airship's gondola wheel touched the ground, causing the bow to bounce up slightly as one final gas cell burned away. At this point, most of the fabric on the hull had also burned away and the bow finally crashed to the ground. Although the hydrogen had finished burning, the Hindenburg's diesel fuel burned for several more hours.

The fire bursts out of the nose of the Hindenburg, photographed by Murray Becker.

The time that it took from the first signs of disaster to the bow crashing to the ground is often reported as 32, 34 or 37 seconds. Since none of the newsreel cameras were filming the airship when the fire started, the time of the start can only be estimated from various eyewitness accounts and the duration of the longest footage of the crash.

Some of the duralumin framework of the airship was salvaged and shipped back to Germany, where it was recycled and used in the construction of military aircraft for the Luftwaffe, as were the frames of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II when both were scrapped in 1940.[6]

In the days after the disaster, an official board of inquiry was set up at Lakehurst to investigate the cause of the fire. The investigation by the US Commerce Department was headed by Colonel South Trimble Jr, while Dr. Hugo Eckener led the German commission.

Hindenburg disaster sequence from the Pathé Newsreel, showing the bow nearing the ground.

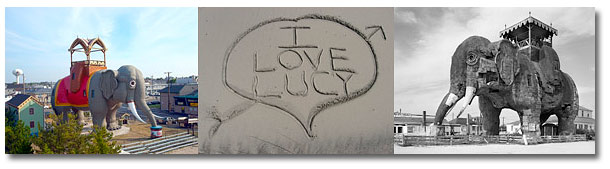

LUCY THE ELEPHANT

Chapter 1 – Elephant to Starboard

The outer islands of the Southern Jersey coast are romantically entwined with legends of pirate chieftains fighting battles to the death on sandy beaches, of buried treasure beneath every dune, of whalers rushing for boats when the cry of "Thar' She Blows" echoed from lookout stations. Mysterious cargoes landed in the dead of night and were quickly gathered by horsemen who disappeared in the deep shadows of the pines, according to legend. Pages of the past are so cluttered with this type of adventure that even dedicated historians are hard put to separate fact from fiction. However, no legend of the colorful Southern Jersey seashore history matches the sight of a 65-foot high wooden Elephant astride the beach looking out into the mists of the sea, a spectacle that according to historians made many coastwise seamen of the tramp ships from the West Indies swear off their rum rations for days.

There is the story of one young seaman on his first voyage who had the early evening watch as his ship made it up the coast on its way to New York harbor.

After first reporting "All's well" he suddenly yelled "Elephant!!”

The captain thinking the seaman had gone berserk rushed to the deck. Lifting his long glass to the shoreline he also exclaimed: "Elephant!", wiped off his glass and after a second look confirmed the fact that there was a giant beast standing among the dunes and eel grass of lower Absecon Island. The captain's report at anchoring in New York harbor brought a score of news people and the curious southward into New Jersey to investigate. After a long, dusty ride from the upper part of Absecon Island to what was then called South Atlantic City, the investigators found that the Elephant was no mirage. Here it stood in full majesty, king of all it surveyed.

Metropolitan newspapers the next day were telling the story of a wooden Elephant, which later would become known as "Lucy", much to the delight of land speculator James V. Lafferty, Jr., who was responsible for the designing and building of the strange pachyderm. James Vincent de Paul Lafferty, Jr., was born in Philadelphia, Pa., in 1856 of prosperous Irish immigrant parents from Dublin, Ireland. Lafferty, and his wife, Mary Cecelia Tobin, had five children, two of whom died in their childhood. Surviving were Mazie, James III, and the youngest son, Robert.

Lafferty, who grew up to be an engineer and inventor, came into possession of a number of sandy lots in the South Atlantic City area. They were cut off from the frame houses and mule-drawn street cars of Atlantic City, by a deep tidal creek. Only at low tide could anyone make his way down to the sands of his properties. Most of South Atlantic City at that time was a combination of scrub pine, dune grass, bayberry bushes and a few wooden fishing shacks.

Once Lafferty hit upon the Elephant idea he enlisted the aid of a Philadelphia architect named William Free to design this unusual structure he felt would attract visitors and property buyers to his holdings. The Elephant was constructed in 1881 by a Philadelphia contractor at a reported cost of $25,000, which at the time was a considerable amount of money. Lafferty always claimed that before the work was finished the cost Skyrocketed to $38,000.

To protect his original idea, Lafferty applied for and received a patent from the U.S. Government. He made his original application June 3, 1882, and received the patent, No. 268, 503, on Dec. 5, 1882. In his application Lafferty stated: "My invention consists of a building in the form of an animal, the body of which is floored and divided into rooms ... the legs contain the stairs which lead to the body ...". Lafferty also included a paragraph which stated the building "may be in the form of any other animal than an elephant, as that of a fish, fowl, etc." What his intentions were in adding that paragraph have never been clear. He never attempted a building in any of the forms mentioned.

Originally named "Elephant Bazaar," the building is 65 feet high, 60 feet long, and 18 feet wide. It weighs about 90 tons, and is made of nearly one million pieces of wood. there are 22 windows, and its construction required 200 kegs of nails, four tons of bolts and iron bars, and 12,000 square feet of tin to cover the outside.

It is believed that most of the materials were brought to the site by boat, although there was rail service of a sort in the upper part of Absecon Island where the infant resort of Atlantic City was just getting underway. By 1881 Lafferty was placing advertisements in area and Philadelphia newspapers offering building lots in "fast booming South Atlantic City." Lafferty eventually extended himself too far in his land deals both at the Jersey Shore and in New York and by 1887 sought to unload his South Atlantic City holdings. He offered the Elephant and other property for sale and found a willing buyer in Anton Gertzen of Philadelphia. (TO BE CONTINUED)

THE MORRO CASTLE DISASTER

.jpg)

On September 8th in 1934, the passenger liner S.S. Morro Castle ran aground just a few yards from Convention Hall in Asbury Park. One hundred thirty-seven passengers and crewmembers died aboard or while trying to escape from the fire-engulfed ship. Many mysteries still surround the wreck of the Morro Castle, which remains one of the worst maritime disasters in U.S. history. The ship was ravaged by fire of suspicious origin. The beacon of the Sea Girt Lighthouse enabled the crew to fix their position before they dropped anchor three miles offshore. Then, as people went overboard, the blinking light guided them to shore and gave them hope as they fought for their lives.

People in coastal towns began calling the Coast Guard, police, and fire departments to report a fire at sea. Many area residents woke that morning with foreboding to the sounds of blaring whistles and sirens as police, fire, and first aid squads responded. Despite storm conditions, fishing boat captains and volunteers took boats out from the docks in Belmar, Brielle, Point Pleasant, and other harbors.

As fishing boats were pulling people from the stormy waters, Morro Castle lifeboats began landing. The first lifeboat to reach land beached at the south end of Spring lake around 6:15 a.m. carring 30 people - 27 crewmen and only three passengers. In all, four Morro Castle lifeboats beached in Spring Lake and two boats beached in Sea Girt. Ambulance crews, police and fire departments—some from up north—arrived in Spring Lake and Sea Girt to join lifeguards and others there who were pulling people from the water.

At Camp Sea Girt, the New Jersey National Guard set up a temporary morgue. More than 100 bodies were brought there. Shore residents and innkeepers took survivors in. Restaurants provided food and merchants offered clothes.

As early as the day after the Morro Castle fire, investigations began. Damning facts emerged and were detailed in official reports and in court. The big question—what caused the fire—remained unanswered. There was a strong suspicion of arson, but most of the evidence needed was incinerated in the fire.

There had been 549 people aboard the ship on its final cruise. The day of the disaster 134 people died—more than 30 percent of the passengers, but under 18 percent of the crew. While suspicion eventually centered on one particular crewman, he was never charged. In fact, no one was ever charged with starting the fire.

Some good came of the Morro Castle disaster. As a result of the tragedy and the investigations that followed, changes were made to shipboard procedures and ship design and materials that improved saftey in ship travel.

On the 60th anniversary of the disaster and rescue, a memorial program was held at the Sea Girt Lighthouse, where the Morro Castle story is kept alive. Tour guides recall the events as visitors fiew Morro Castle photos, documents, and artifacts, including a lifeboat oar and two lifejackets.